Salvaging

Huon Pine

By any comparison or definition, Huon pine trees grow to prodigious ages: the trees do not reproduce until they are 600 – 800 years old, and many specimens can be found which, are well over 2,000 years old.

It would be unconscionable to continue cutting down such precious, historic organisms.

Concern for the future of Huon pine is not new: a Parliamentary Select Committee of Enquiry was held as early as 1879 to explore the Huon pine industry, with particular reference to the age of the trees. From the moment the explorers first found buried logs on the banks of the Huon River before 1810 it was known that we would never get another generation of these trees to use. Plantations were out of the question: we had to make the most of the timber we had.

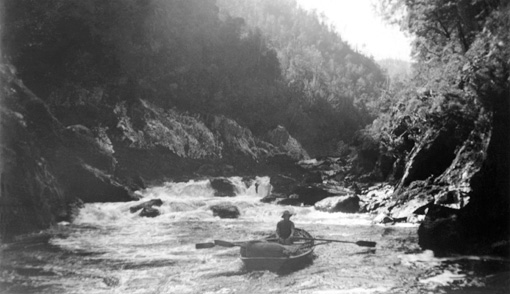

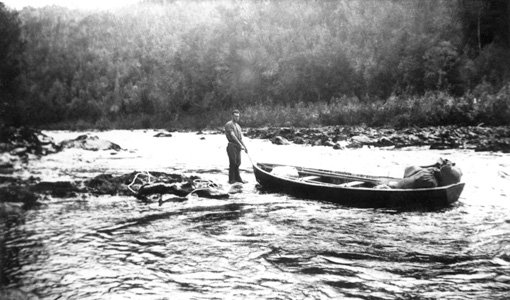

This knowledge has driven the Huon pine industry, especially for the past 60 years. The timber’s unique capacity to withstand rot for hundreds and even thousands of years, and its ability to float even as a green log has enabled salvage processes unheard of in other timber industries: Between 1970 and 1990 about a dozen large and small lakes were created by damming western rivers for hydro electric impoundments. Huon pine trees in the path of the flooding were cut down and put into stockpiles for later use; once the timber was saved from flooding there was no urgency to use it quickly, as long as it was kept safe. The stockpile created when Lake Gordon was flooded in 1972 still supplies the majority of Huon pine logs released to the three licensed sawmillers every year.

Photographs from Morrison Family Collection

Salvaging Locations

Some salvage operations, however, are more fortuitous than strategic: When the workers entered the Teepookana forest in 1995 to retrieve stumps and heads of trees left over from historic pining operations, nobody could have known how many intact logs were lying, untouched, under the forest floor. Equally, the piners who left the Rocky Sprent River for the last time in 1950 could not have known that it would take almost 60 years for the logs they cut to be washed free of log jams and down into the Gordon River, where they have been collected up into rafts and painstakingly towed back to Strahan, a living embodiment of the area’s unique history.